Breakfast in America

Aaron Spangler, Amy Thielen, Avery Wheless, Erick Medel, Hannah Lupton Reinhard, Jay Miriam, Jess Johnson & Simon Ward, Kuo Yen Fu, Lanise Howard, Lisa Signorini, Michael Vasquez, Naive John, Reko Rennie, Scout Zabinski

September 19 – October 16, 2021

Fourteen thoughts about Breakfast in America (the ritual and the show)

1. A good breakfast in America is not interesting, thank god.

It is consistent, indulgent, nonjudgmental, universally well-liked, and a thing of beauty. The plates are overloaded, the eggs just a minute from the griddle, their yolks wet and brimming with emotion, the toast shiny with the promise of butter. There’s nothing novel about it, no evidence of strained creativity. It is compelling and symbolic and comforting, but from a cook’s standpoint, it is not interesting.

2. The art world loves to talk about interesting work, which is usually a rather dull conversation. It comes from a desire to interpret, to lay words over image when no one is asking for it—not the work, and not the artist, whose practice is a defense shield against dreaded, poisonous interpretation. Work that doesn’t try to be interesting will naturally be of interest because it doesn’t have any preconceptions about itself. Work like this (like this around us) doesn’t front.

3. “Of course when people said a work of art was interesting, this did not mean that they necessarily liked it–much less that they thought it beautiful. It usually meant no more than they thought they ought to like it. Or that they liked it, sort of, even though it wasn’t beautiful. Or they might describe something as interesting to avoid the banality of calling it beautiful.” — Susan Sontag

4. I’m not talking about boutique hotel breakfasts where you can choose between the acai bowl, the green smoothie, or the tweaked eggs benedict. I mean the place down the street. The hash brown palace, where the booths are worn down in the middle like the concave marble steps of Pisa. There’s no mirror in the place, no espresso machine, just an 8-foot griddle where everything cooks together communally, the edge of your egg and my sausage patty casually touching.

5. Breakfast in America is a meal for workers, and a place for them, too. Sweaty or Suit-y or all in your head, any kind of work will do. The business of collective eating runs a little pre-industrial revolution, all the way back to the trencher. Who doesn’t use their toast to push around and scoop up the eggs?

6. Hate to say it, but in general, Americans don’t know what to eat. The choices are too vast, the grocery stores too big, the menus too large. Diners distill the choices to a more manageable recombination of a few basic ingredients: eggs, potatoes, butter, bread, smoked pork.

7. “This freedom of choice in America is driving us all crazy” — X the band

8. A diner promises community without the sticky complications of family. Unlike a nighttime restaurant with its formal host stand, there are no relationships here. No server-led information sessions. No sommelier, smooth and fired-up with knowledge, swooping around the table like a pirate. The servers in diners are not paid to coach or to mother. If you ask a veteran server where to sit you might get a look that says, “I think it’s time you go to the big-kid bathroom all by yourself now.” No, you walk into a diner and take your place in it. In the diner, we are all insouciant, long-lost drunk uncles, ambling in after a ten-year absence to reclaim our old favorite booth like we hadn’t missed the last two Christmases, like nothing ever happened.

9. This country breaks into two sections along the hash brown line. West of Ohio, you find hash browns; East of Ohio, home fries. Hash browns are Western. They need space, air, big skies, the tops cracking like an old hard top, the interiors as soft and white as ticking. East-coast home fries—potatoes, peppers and onions frying together on the griddle—are humid, like the foggy valley between tight New England towns. Home fries are a little sweet, hash browns a little salty.

10. Some people consider salting to be a matter of personal preference. Others believe in a common mean, a universally standard level of seasoning that the great majority of human palates will recognize as correct. This difference in worldview spans nearly every art, every discipline. The big question lurking behind it is what constitutes art? Mike Kelley made a wall hanging of hundreds of plush toys sewed together—how was that any different from the arrangements of plush toys that sanitation workers strung up on the fronts of their garbage trucks? How about Joseph Beuys flannel suit hanging on a wall? Or Robert Gober’s toilet sculptures? In theory I believe that anyone can do anything—make art, play in a band, cook—but maybe not everyone should.

11. I don’t think that thing that causes the hearts of a group to beat in unison has nothing to do with money, or class, at all. I think it’s taste. Discernment, I suppose you could say, although that implies cultivation and high breeding. Good taste arrives at birth, equally, to all. Sometimes life and the grind wear it down, and sometimes it perseveres anyway.

12. I mean, most of us agree that the first potato chips out of the bag are delicious but that the twentieth is too salty. You either put down the bag half-finished--or finish it, crumple up, and set out in search of water. I sometimes wonder if the chip-makers set the salinity at the height of the threshold just to pick a bone, to start an argument between you and the next chip, as if they know there’s no relationship more addictive than a dysfunctional one.

13. *Kenny Shopsin’s rules from Shopsin’s General Store, NYC

No parties of more than four

Everyone has to eat

No copying the order next to you

Don’t ask for the best thing on the menu

No sharing

No special requests

No assholes

“Most of the times when a customer makes a special request, it’s not about the food, but rather his own desire to be in control and to establish his own specialness. Making people feel special through this kind of ass-kissing is one of the services that a restaurant can provide, but it’s not a service that I want to provide. Some people tell me that they’re deathly allergic to something and I have to make sure it’s not in their food. I kick them out. I don’t want to be responsible for anyone’s life-or-death situation. I tell them they should go eat at a hospital.” — from Eat Me: The Food and Philosophy of Kenny Shopsin: A Cookbook (Knopf, 2008)

14. Kenny reminds me of Linda of the famous Linda’s Antiques, a warehouse-sized thrift store in my rural northern Minnesota hometown. Linda doesn’t take any shit, either. I mean, she will accept your shit, your personal cast-offs, for store credit and resell them, but she won’t accept any attitude inside her store. If you bring an item to the counter and open your wallet to pay full price, she’ll reward you with a few dollars off, for good behavior. If you ask her if she’d take 4 dollars for a 5-dollar vase she’ll run you out of her store. Who asks for a discount on an already-cheap used vase? It’s not a garage sale. It’s respectable place. If you don’t have manners, Linda will teach them to you. Favors can’t be demanded. They’re given, freely, as gifts, and good people already know this.

Amy Thielen

September 2021

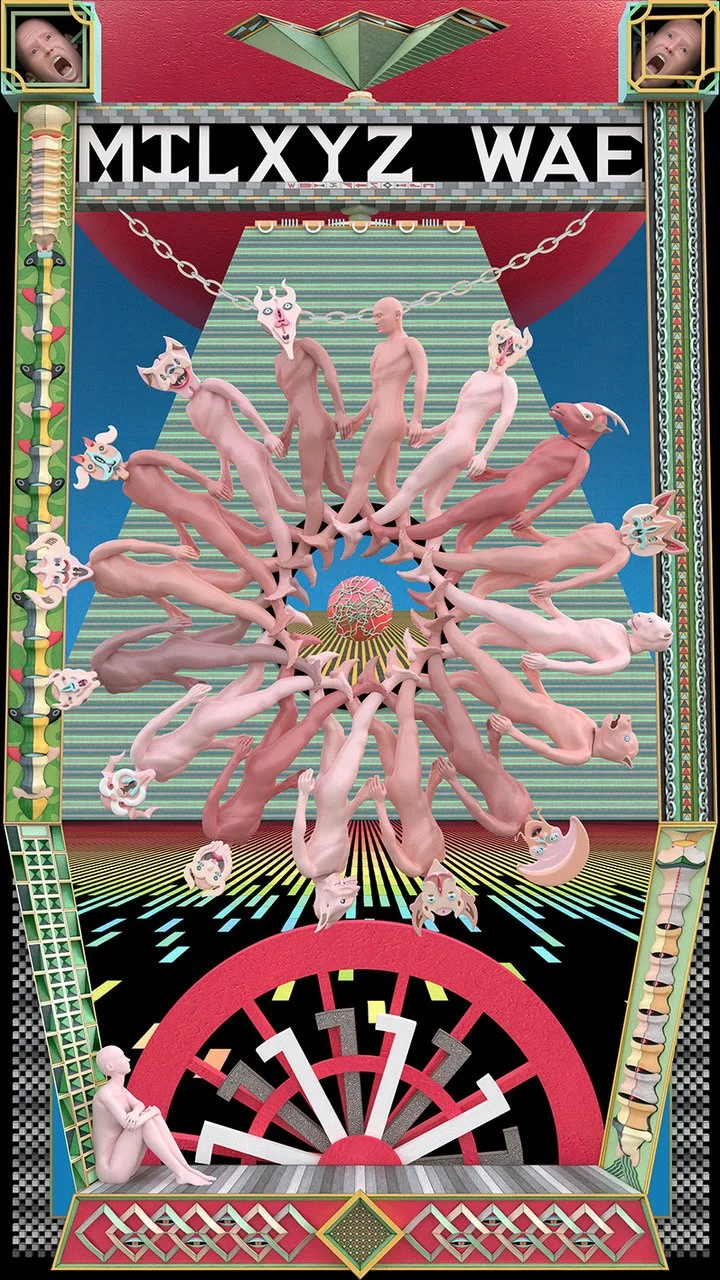

Michael Vasquez

The Rooster’s Crow - Neighborhood Watch (Zombie Shift), 2021

collaged acrylic on paper over panel, pulp-dyed colored paper, and PH-neutral adhesive

80 x 66 x 1¾ in.

203.2 x 167.64 x 4.45 cm