Age Before Beauty: LeRoy Neiman’s sketches from the set of the Rocky films

November 27, 2020 – February 10, 2021

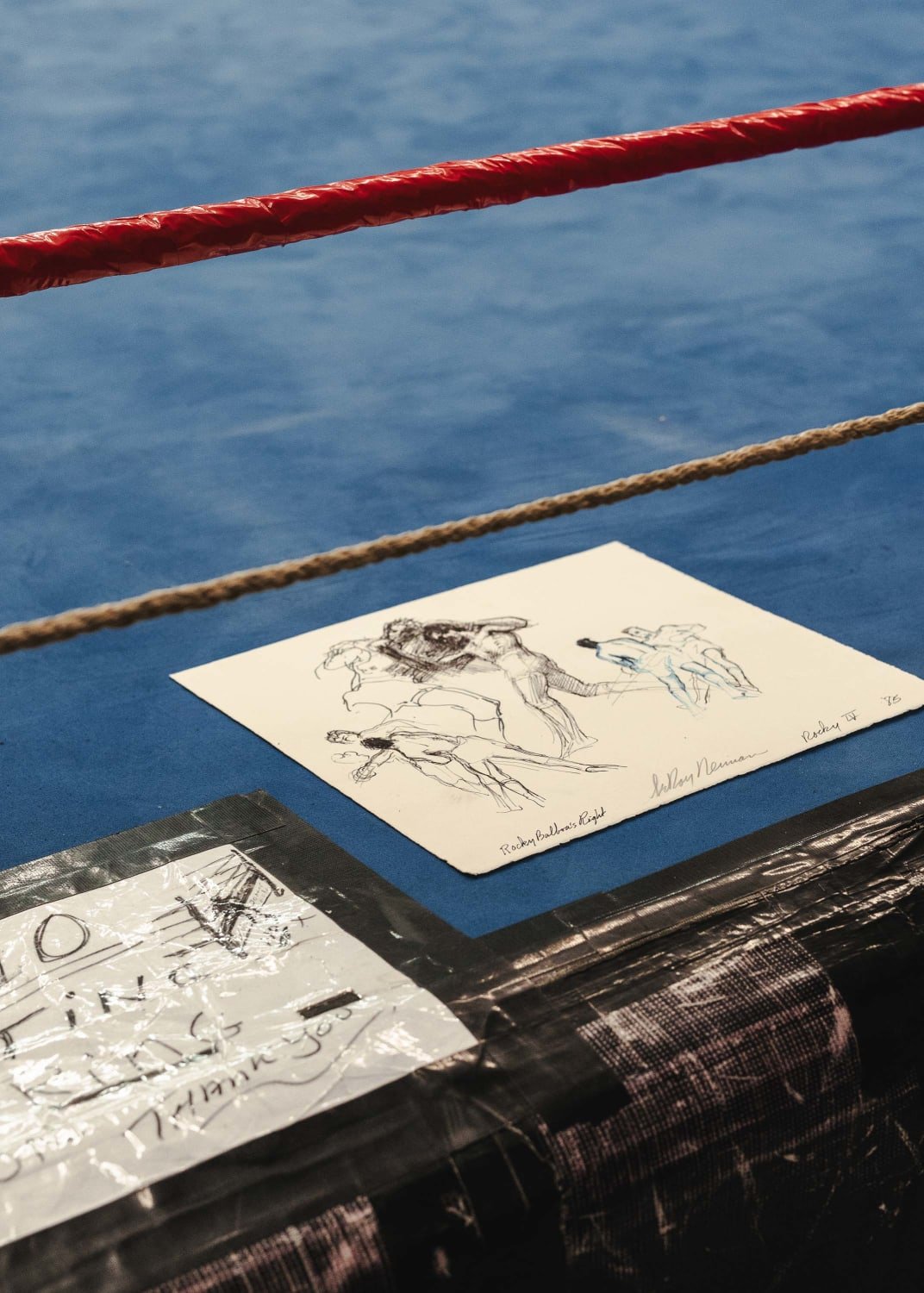

The LeRoy Neiman and Janet Byrne Neiman Foundation and Rusha & Co. are pleased to announce Age Before Beauty, an exhibition of LeRoy Neiman's sketches from the set of the Rocky films, staged at Gleason's of Brooklyn, the world's most famous boxing gym. The show opened as an immersive online experience at Rusha & Co. on November 27, 2021 the 35th anniversary of Rocky IV's debut in theaters, through February 10, 2022.

_____

Film historians will tell you that the most important and influential freeze frame ending in cinema history is Truffaut’s in Les Quatre-cents coups: Jean-Pierre Léaud, walking on the beach as the character Antoine Doinel, catches the “eye” of the camera, breaking the fourth wall as we and he alike contemplate his uncertain future. Probably so! But for a suburban American kid whose movie education began at the mall, the truly quintessential freeze frame finale—the image on screen for about three minutes of credits, and in my skull for a lifetime—is the one that closes Rocky III. In a boxing gym after hours, with no one else around, Rocky and his former-nemesis-turned-devoted-trainer Apollo Creed climb into the ring for an “extremely crazy” (says Rocky) “mentally irregular” (says Apollo) secret fight. The two men circle each other, bouncing on their toes, trading jokes and boasts until they finally come together mid-ring, swinging simultaneous haymakers at each other’s heads, and…FREEZE! Wow—talk about an uncertain future…

But Sylvester Stallone (who directed Rocky III, as well as writing, starring in, and building himself an ultra-shredded new physique for the film) is not the kind of auteur to leave a good thing alone if he thinks he can supercharge it, so he optically zooms in on that frozen shot, then crossfades to the same image rendered in a stunning splash of bright oil paints—the dim, drab light of the gym transformed into a crazy quilt of red, orange, green, blue, half of Apollo’s chest a blazing yellow—and the artist’s signature, bold and brazen across Rocky’s shorts: LeRoy Neiman.

Stallone had placed extraordinary faith in LeRoy Neiman. This was the movie that introduced both Mr. T and “Eye of the Tiger” to the world—how many painters leap to mind who’d belong in that company, who could be relied upon to make you pump your fist in the air? Furthermore, Stallone happens to be a painter himself—if you have ever heard him croon the theme to Paradise Alley (“Too Close to Paradise”), you’ll know he is not shy about taking on an additional job when there’s no one else he trusts to bring his spirit to it. But in Neiman, he had clearly found an essential collaborator—like Carl Weathers as Apollo, Talia Shire as Adrian, or composer Bill Conti, Neiman understood exactly what the Rocky universe required and he delivered it, big time. The painting is brash, unforgettable, and like Rocky IIIitself, couldn’t give less of a damn whether or not you find it “tasteful.”

The painting recurs in the later franchise film Rocky Balboa and then the ensuing Creed series, its enormous canvas filling the back wall of a memorabilia-filled restaurant that the older, humbled Rocky character now owns and runs for a living. Of course this makes no kind of logical sense—why would Rocky own a painting of a fight that no one except he and his dead mentor even know happened?—but the metatextual flourish makes perfect emotional sense, or “Rocky” sense at any rate, and signals Sly’s obvious gratitude and loyalty to his kindred spirit.

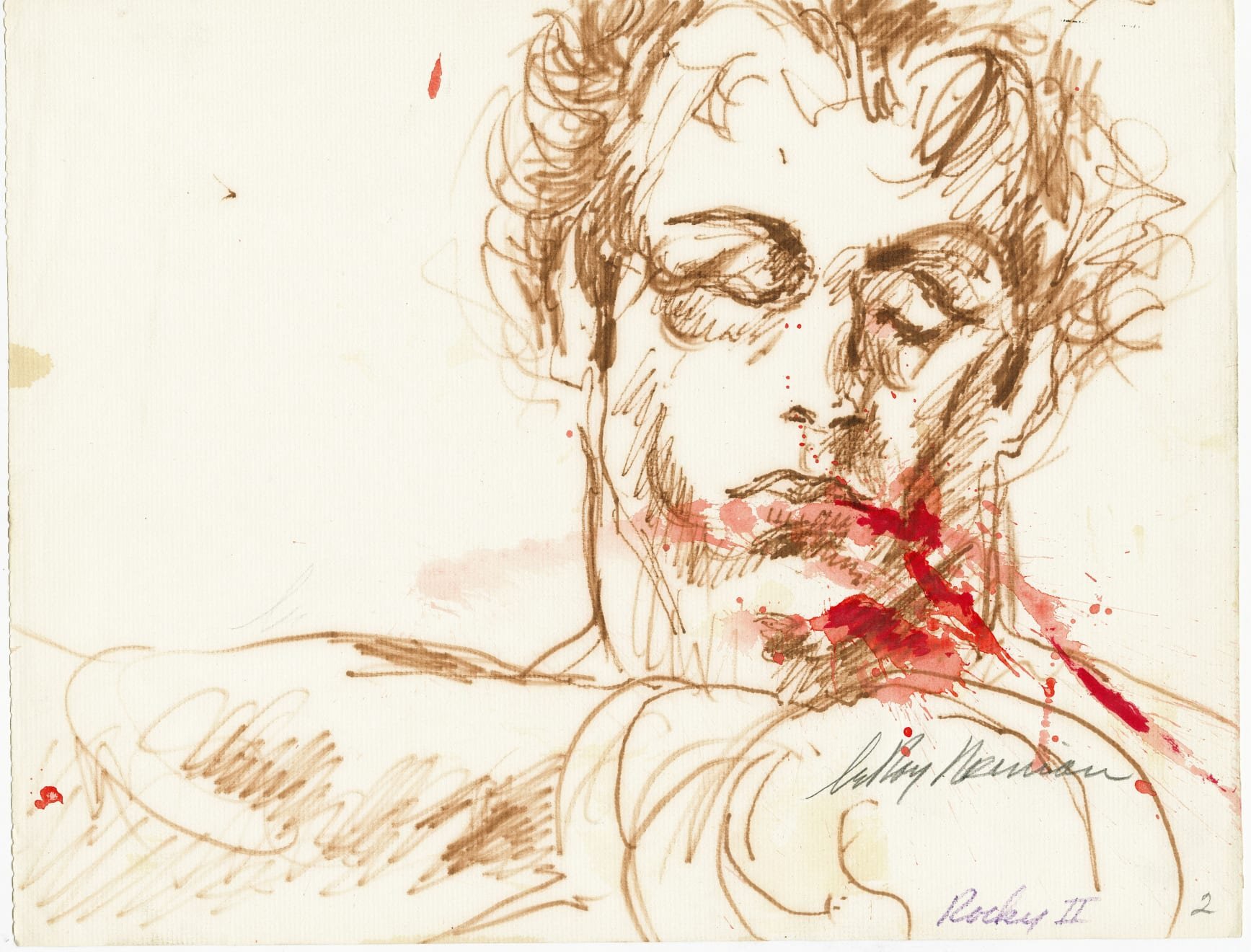

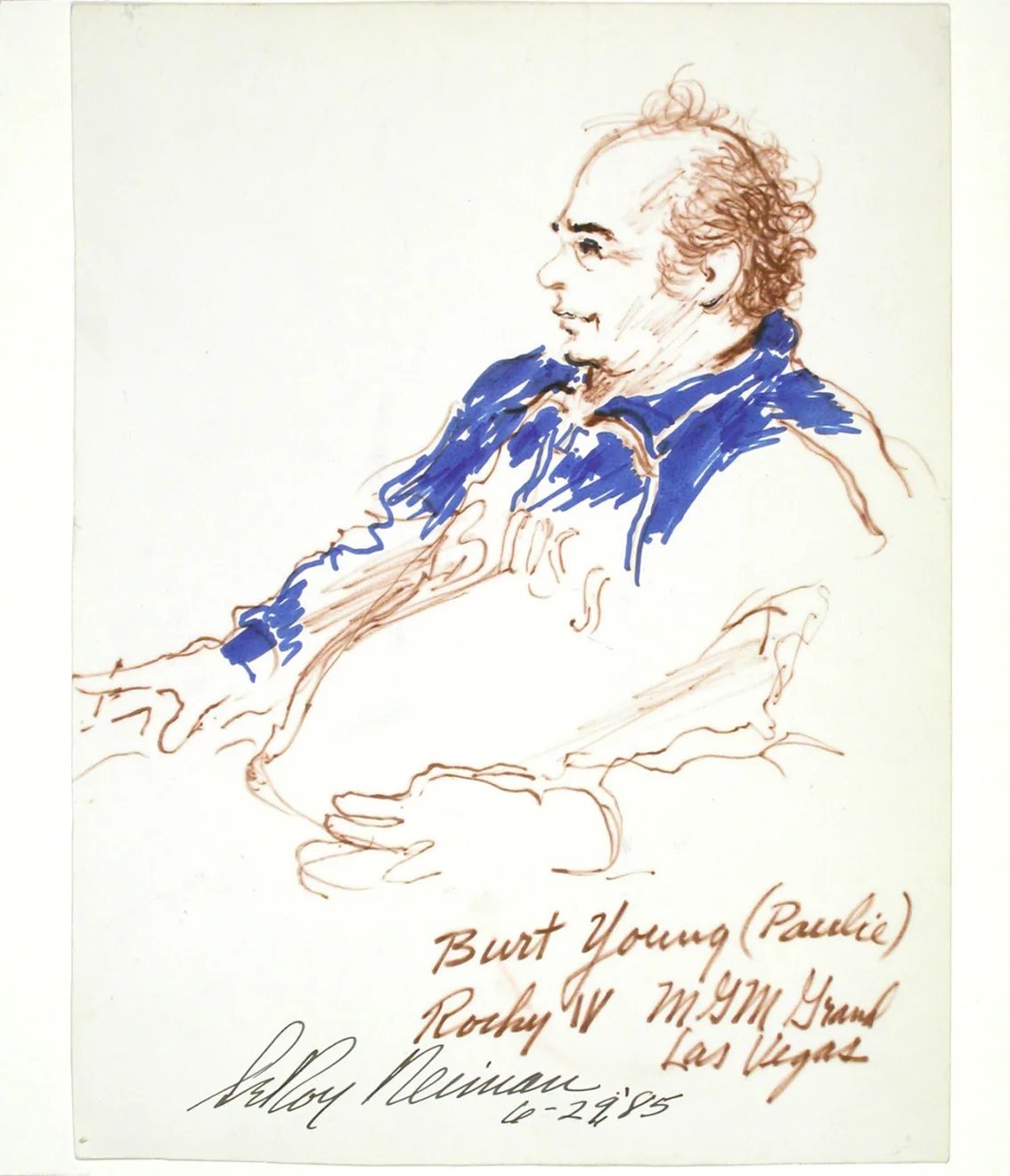

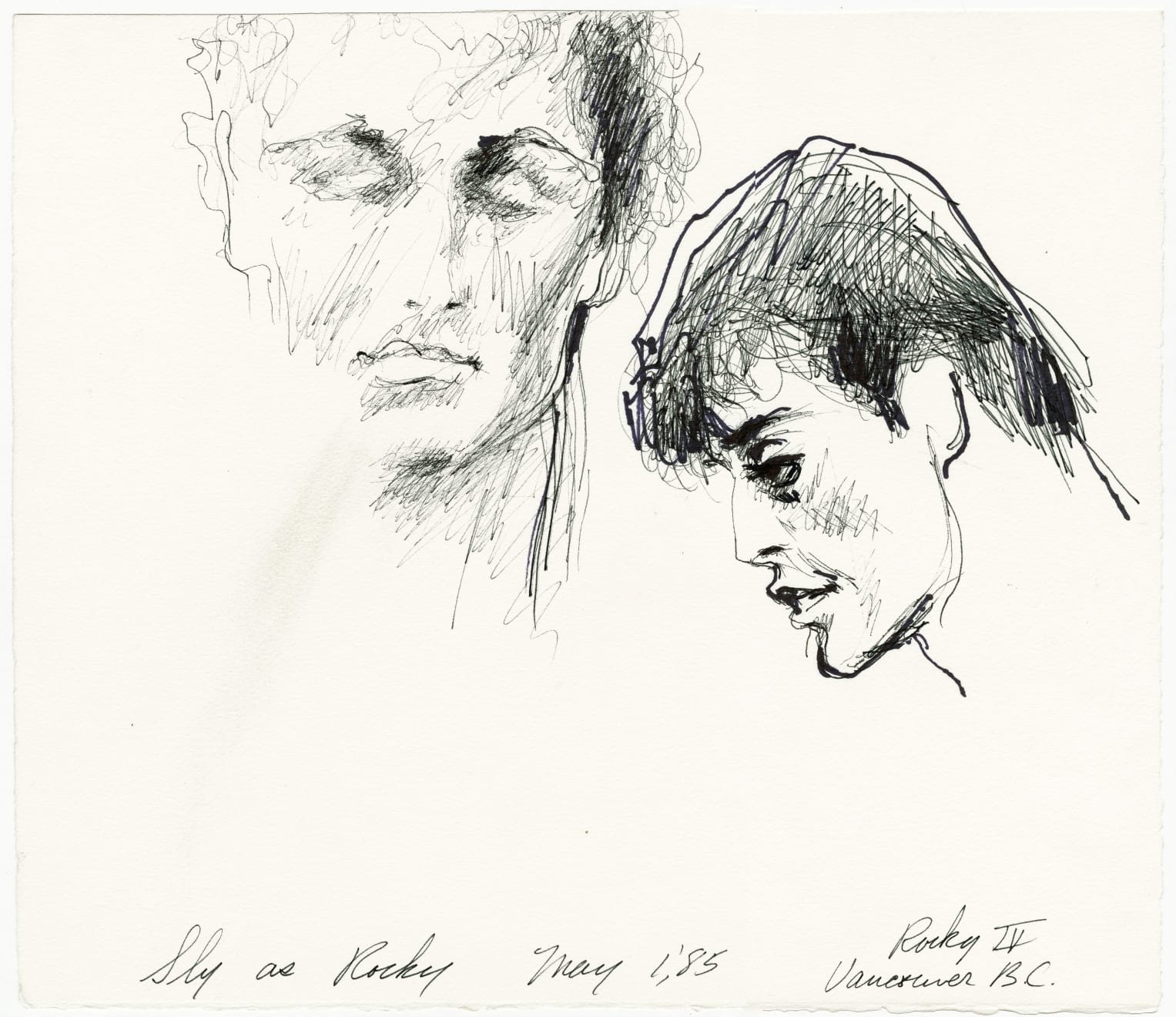

Neiman was present on the sets of all the Rocky movies shot in his lifetime except the first. Ever the compulsive sketcher (a workaholic and a playaholic), the hours he spent haunting the productions resulted in stacks of drawings and paintings. A few of these turned into works he exhibited publicly which, like “Rocky Vs. Apollo”, went on in poster form to adorn mancaves and dorm rooms worldwide, while many, many others were never intended for public consumption. To go through these private pages now is an unparalleled treat for the Rocky fan: We are witnessing one wildly instinctual, optimistic pop artist cavorting in a playground built by another. Neiman—who knew the world of real life boxing very well, counting Muhammad Ali among his pals (and having encouraged the champ to take up drawing)—clearly delights in his peek behind the curtain as Stallone makes movie magic from men pummeling each other, and his brushes, markers, and pens race to transmit the thrill to paper. Sometimes his studies are quite developed (the view from the stadium floor as Rocky stands above a conquered Ivan Drago suggests an epic canvas), while others move like blurry snapshots: quick glimpses of fight choreography being rehearsed, actors between takes awaiting their call to set, extras and cameramen finding their positions.

Check out Carl Weathers, as Apollo, sitting on the floor with back arched and arms around his knees in an almost fetal position. The poetry of the moment must have been particularly striking, as Neiman didn’t even wait around for a clean piece of paper—he’s sketched it right atop the shoot day’s call sheet, from the looks of it perhaps indeed the very day Apollo “died” by Ivan Drago’s merciless attack. What was Neiman seeing? Is the actor, between takes, contemplating the passing of a beloved, career-defining character with whom he has lived for nearly a decade?...Or is Weathers just contemplating the apparently topless woman on the other side of the page? (She does not appear to be Sylvia Meals, present and playing Mrs. Creed that day. She might have been one of the showgirls or round card girls in the Vegas-set scene. Or perhaps just Neiman’s imagination wandering off from the sweet science…Despite the massive popular success he attained in his half century career, Neiman did always hang onto his day job sketching fantasy “femlins” for Hugh Hefner’s Playboy…)

“I’m a believer,” Neiman has been widely quoted as having said, “in the theory that the artist is as important as his work.” Stallone surely agreed, and invited his friend to essay multiple cameos across the series. Neiman, always fascinated by performance, who achieved so many of his own greatest glories representing athletes and musicians at peak flexing of their powers, was happy to show up and play. As he well knew, his famous mustache (echoing and rivaling Salvador Dali’s facial-hair-as-synecdoche-for-persona) was perfect for the silver screen, a found material to delight any director.

Stallone repays the favor as Neiman’s most frequent subject here—big hangdog eyes, full lips, hard jaw—strangely majestic on the page even as his features threaten to droop off his face. Neiman leans in to a heroic look for Sly (a comic book “POW!” wouldn’t look out of place on some sketches of Rocky slugging Drago) because he knows, and loves, that they have all assembled to construct a mythology together. Carl Weathers, Burt Young as Paulie, Tony Burton as the constant trainer Duke—they’re all woven now into the dreams of millions who invested their hearts in these stories. And who’s this shadowy figure we see bottom left in the rendering of “Round XV” of the Balboa-Drago fight? As a cornered Drago suffers the sting of Rocky’s left cross, a spectator below gazes down at his sketchpad, pen in hand, cigar jutting out from beneath a dark patch of heavy mustache…Freeze frame here as the fourth wall shatters again. LeRoy Neiman’s right there in the story, and the story is in him.

Written by

Andrew is the writer/director of the films Funny Ha Ha, Mutual Appreciation, Beeswax, Computer Chess, Results, and Support the Girls. He has previously written on the Rocky films, for The New Yorker.

With thanks to

Gleasons - of Brooklyn, the world's most famous boxing gym.

Grace Rivera - for all images shot at Gleasons.

LeRoy and Janet Neiman Foundation - for all the support and collaboration on this show.

Assorted photos and archival material copyright of LeRoy Neiman and Janet Byrne Neiman Foundation

Select photos by Lynn Quayle.